Let me preface by saying that this post is quite a bit different than the others, and comes with the proverbial “viewer discretion advised” warning.

While it doesn’t focus on a lost business or restaurant per se, it’s a tragic story still quite relevant to Laurel’s retail history. For me, at least—because the “Missing Person” flyers I saw at Zayre, the mall, restaurants, gas stations, drug stores, and nearly everywhere else in Laurel as a child thirty years ago this week have certainly stayed with me. And a large part of what has fascinated me about this incredibly disturbing case—which remains open to this day—is how very little has actually been written about it in the thirty years since.

Like most Laurel children in 1982, I first heard about the Stefanie Watson case in brief, sanitized tidbits from my parents. It was scary stuff, to be sure—even for adults. Rumors and speculation abounded in the days and weeks after 27-year-old Stefanie Watson mysteriously vanished on July 22, 1982.

The general “facts” as I knew them at the time were stark… and terribly grim: she had worked at the Greater Laurel Beltsville Hospital; her car was found near Laurel Centre mall several days later, saturated with blood; and even more chilling, her head was discovered over a month later in the woods at the end of Larchdale Road. That’s all I knew then, and that’s really all I’d known ever since, until I began to revisit the crime myself earlier this year.

I imagine the details of Stefanie’s name and face have faded from some memories over the past three decades, but I’m positive that anyone—like me—who lived in Laurel at the time of her murder has never truly forgotten.

I was too young to read the newspapers or listen to the news reports, but word spread fast throughout Laurel in the wake of Stefanie’s disappearance. School was out for the summer at the time of her apparent abduction, but with the grisly skeletal discovery on September 3rd, I can remember Deerfield Run Elementary being on high alert. Letters were sent home to parents, advising caution—particularly for those who walked to school. Her murder came on the heels of the high-profile abduction and decapitation of young Adam Walsh just one year earlier. Deerfield Run administrators had sent letters home to parents then, as well.

I didn’t know it at the time, but one of the last places Stefanie Watson had been seen alive on July 22nd was at the Town Center Shopping Center, just a short walk away from my school on Rt. 197 and Contee Road.

That summer, I saw the missing person flyer often. I can still envision it taped to the front entrance window of Zayre, where I frequently stood for hours, hawking the wares of the fabled Olympic Sales Club—from whom I hoped to win the equally fabled prizes or cash.

That was one of my first “jobs”, selling these Olympic greeting cards and gifts. After canvassing every building in Steward Manor, I ventured over to Zayre to catch people as they entered.

It was during the frequent lulls of approaching Zayre customers (i.e., unknowing prospective Olympic Sales Club customers) that I couldn’t help staring at the Stefanie Watson flyer; I’d read it again and again, trying to grasp what could have possibly happened to the pretty lady whose photo seemed to watch over me protectively as I timidly repeated my sales pitch to strangers—any of whom, I feared, could’ve been the person responsible for her disappearance. I walked to Zayre from Steward Manor nearly every day that August to make my sales, and Stefanie Watson’s smiling face was always the first and last thing I saw there.

I soon learned that my uncle, Art, had worked with Stefanie at the hospital and knew her casually. Between my youthful innocence and his probable shock over losing a colleague in such a traumatic way, Art didn’t really say much about the matter. Not that I could blame him. He simply remembered her as being very nice, really friendly, and well-liked; and he was working that Thursday night—part of the cleaning crew—when she failed to show up. “It was also supposed to be her last night at work,” he said. “She was getting ready to move to Texas.”

When Stefanie’s 1981 Chevette was discovered in the Middletown Apartments parking lot the Monday after her disappearance, my Steward Manor friends and I knew about it before our parents did. Some of the “big kids” had been at the mall and witnessed the flurry of police activity across 4th Street. Some ventured close enough to see the blood—and they eagerly told us what they’d seen. They were convinced, as would soon be the police, that Stefanie wasn’t going to be found alive.

(Laurel Leader)

The gruesome drama seemed to be unfolding in three acts over the course of that summer: Stefanie’s disappearance and the grisly discovery of her car were acts one and two, respectively. The third and final act came on September 3rd, when police recovered partial skeletal remains—which they delicately conceded was only the head of the victim. That shocking find was made in the wooded area at the dead end of Larchdale Road—a location that would once again haunt me some four years later during yet another childhood summer job. I was a paperboy briefly for The Washington Post, and my pickup point was outside James H. Harrison Elementary—on Larchdale Road—at midnight. Few experiences before or since have unnerved me as much as sitting there alone in the dead of night under that fluorescent din, hurriedly stuffing newspapers into plastic bags less than 100 yards from where Stefanie Watson—her head, at least—had been found. Yes, Stefanie Watson crossed my mind quite often that year.

But then the years began to pass. Decades passed, in fact. As far as I knew, nothing else had ever come of the Stefanie Watson case. No one was ever charged with her murder; and worse, the rest of her body was never recovered. At some point during my research for Lost Laurel, the spectre of Stefanie Watson’s murder once again creeped into my mind.

Still curious after all this time, I began to search online for anything related to her case—news articles, updates, blog postings—anything. I was surprised to find only one single website that even mentioned Stefanie Watson—and despite best intentions, it had misspelled her name and stated the facts incorrectly.

A footnote buried deep within an online memorial page for Maryland homicide victims. Sadly, that was all that seemed to be left of Stefanie Watson. I found it hard to fathom that such a shocking crime could go so long without at least some kind of press coverage, especially when you stop to consider the almost Hollywood-like circumstances of her murder. On paper, the case reads like a James Ellroy novel: a beautiful, young blond woman fails to show up for her last night at work before leaving town… After going missing for nearly a week, her bloodstained car is found; and several weeks later, only a partial skull is recovered. There are no apparent suspects, no arrests, and the crime quickly falls into the cold case files. To put it even more bluntly, a woman is decapitated—in a peaceful, middle-class DC/Baltimore suburb, and this crime goes virtually unmentioned all this time? Are you kidding me? This should’ve been on CNN and on magazine covers across the country. Books should’ve been written about this.

Knowing that the 30th anniversary of Stefanie’s murder was approaching, I finally started looking into it in earnest myself.

I began by speaking to friends and acquaintances who remembered the events of 1982 at least as well as I do. Online, I was only able to find brief articles in the Washington Post and Baltimore Sun‘s archives, but a treasure trove came via the Laurel Leader on microfilm. There, on the analog monochrome screen at the Laurel Library, was the full weekly saga from July to September 1982. I was about to discover the Stefanie Watson case all over again—reading the details as they emerged that harrowing summer thirty years ago.

1. Who Was Stefanie Watson?

Before we get too far into this, let’s start by shedding some light on just who Stefanie was. Clearly more than just a face on a missing persons flyer, she was someone’s daughter, sister, friend, and colleague. She had also briefly been someone’s wife. By all accounts, she was a kind and gentle young woman. Her uncle, Wilhelm Mabius, remembered her as being “reserved, yet lighthearted and happy-go-lucky.”

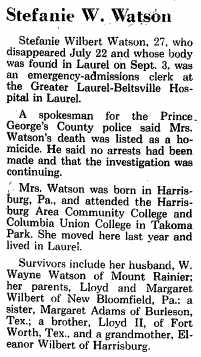

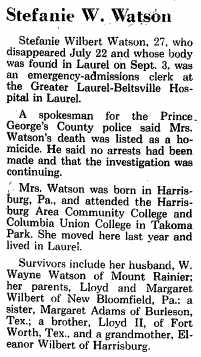

She was born Stefanie Wilbert in Harrisburg, PA in 1955, and was 27 years old at the time of her disappearance. A graduate of Central Dauphin East High School in Harrisburg, Stefanie had also attended Harrisburg Community College. She came to the Washington, DC area to attend Columbia Union College (now Washington Adventist University) in Takoma Park in September 1981, and settled in Laurel after her brief marriage to W. Wayne Watson ended in separation. (Mr. Watson was quickly and definitively ruled out as a suspect).

Stefanie’s 1973 high school yearbook; the year she graduated.

Stefanie’s senior yearbook photo, 1973.

Stefanie’s first name was commonly misspelled, as her previous yearbook photo (1972) attests.

Stefanie held a number of jobs, working as a clerical typist and in a dentist office prior to becoming a night admitting clerk in the busy emergency room at Greater Laurel Beltsville Hospital—a job that she rightly considered much more than simply filling out insurance forms. Colleagues recalled that she never failed to console families of the sick and injured, bringing them coffee and allowing them the chance to talk about their anxiety and grief. One staff doctor noted the countless cases of “gratuitous and senseless violence” that the emergency room saw on any given night shift; and that Stefanie Watson was always “caring and concerned for all the people she met… ingenuous and never cynical,” even when patients or their families seemed undeserving of her patience and thoughtfulness.

In Laurel—the town experiencing a renaissance of sorts in 1981, with the recent opening of Laurel Centre Mall, the newly-restored Main Street, and the advent of the annual Main Street Festival—Stefanie found a place to heal the wounds of her broken relationship. She lived alone with a large dog at 304 8th Street, Apt. 1.—a short drive from her job at the hospital.

Stefanie’s apartment building today.

While Stefanie had worked there for nearly a year when she went missing, few of her hospital coworkers had gotten to know her particularly well. Still, it was these colleagues who created the missing person flyers, and with the cooperation and approval of Laurel Police, distributed them to practically every local business in sight. As they did so, a surprising number of people actually recognized Stefanie’s photo from her job at the hospital, and immediately recalled her kindness at times of their own personal crises.

Stefanie’s coworkers had given her a going-away party at the hospital on Wednesday, July 21st—the night before her disappearance. She had made the difficult decision to move to Fort Worth, Texas, where she was to begin working at the Medical Plaza Hospital on August 3rd. Stefanie’s relatives said that her decision to leave Maryland was made because she wanted to be closer to her brother and sister’s families, both of whom lived in Texas. She was also looking forward to getting to know her five young nieces and nephews, the youngest having been just six months old at the time.

Stefanie was planning to leave for Texas on Monday, July 26th. Instead, that would turn out to be the day that her blood-stained car would be found on Fourth Street.

2. Last Sightings

According to police reports, Stefanie was seen multiple times on Thursday, July 22nd—more than the Washington Post‘s report of her having last been spotted alive at the hospital that afternoon, when she picked up her paycheck.

(Washington Post. July 27, 1982, p.B2)

(Washington Post. July 31, 1982, p. B2)

In fact, the Laurel Leader later reported two additional key sightings as confirmed by police: one by a hospital coworker who saw Stefanie at a bank at Town Center Shopping Center on Route 197 and Contee Road that afternoon (perhaps depositing the paycheck she’d picked up earlier at either the Citizens National Bank or John Hanson Savings and Loan that were in the shopping center at that time); and the other, more crucial sighting—detectives established that she was actually last seen at 9:00 PM, leaving her apartment.

Whatever happened to Stefanie occurred that night, after 9:00 and before she was due to report to her final night shift at the hospital.

3. Murdered.

After six long weeks of speculation and angst, the worst fears of Stefanie Watson’s relatives, friends, and all of Laurel were confirmed. On Friday, September 3rd, police discovered “partial skeletal remains” in the wooded area at the dead end of Larchdale Road.

Initial reports stated only that it was a citizen who made the grisly discovery, and on Tuesday, September 7th, the Maryland Medical Examiner’s office confirmed that the remains were indeed those of Stefanie Watson. Positive identification was made with dental records, according to then Laurel Police Lt. Archie Cook, who had headed the investigation to that point. He tactfully declined to elaborate on the physical condition of the remains, only to say that various television reports—likely about the partial skeletal remains being only the head—were unconfirmed.

(Washington Post. September 8, 1982, p. A26)

The discovery on Larchdale Road marked a transitional phase for the investigation, as Prince George’s County Police essentially took over the case. The crime scene was determined to be in an area of Laurel under county police jurisdiction. Sgt. Sherman Baxa of the Prince George’s County Homicide Unit credited Laurel Police for “Collect(ing) a tremendous amount of data”, and for cooperating with the P.G. County detectives as they assumed the reins of the investigation.

Sgt. Baxa later released some compelling information about the citizen who’d found the partial remains. He’d witnessed a man actually throwing them into the woods.

Baxa stated that the wooded area at the end of Larchdale Road had been used as a “dumping ground” for debris for some time, but the witness who found the remains had “observed an individual throwing something in the woods.” He said that the witness became curious, later walked over to the wooded area, and subsequently made the startling discovery. The witness was never publicly identified for obvious safety reasons, but it’s presumed that he was a resident of the nearby Larchdale Woods apartments (now known as “Parke Laurel”). Whether he happened to be walking by, in his car, or looking out a window wasn’t released; and while he couldn’t positively identify “the individual” he’d seen dumping “debris” in the wooded area, he’d provided police with even more critical information: he’d seen the car the suspect emerged from… and he’d seen a second man inside.

(Laurel Leader. September 16, 1982)

4. Meanwhile, thirty years later…

Let’s cut back to the present day, since it was only this year that I learned details I hadn’t previously known. As a child, I wasn’t even aware that a witness had seen the car, or that police had released a composite sketch of the man wanted for questioning—a man who never did turn up.

But going back to my initial curiosity, and first asking old friends about what they recalled from the case, it was something that one of the “big kids” (a term we still use for those in the neighborhood who were a few years older than my little clique) said that I found particularly compelling. Mark Nelson, who lived upstairs in my building at Steward Manor in the 1980s, recently told me, “I’d heard somebody say that the guy who killed Stefanie Watson was the same guy who killed Adam Walsh.”

The notion that the same man who’d murdered little Adam Walsh the previous year—all the way down in Hollywood, Florida—sounded like a long shot at best… Until I started looking more closely at just who that man actually was. And when comparing these new bits of information to those old Laurel Leader articles, I actually got chills.

Adam Walsh, 1981.

On July 27, 1981—almost exactly one year before Stefanie Watson’s murder—6-year-old Adam Walsh was with his mother at the Sears store in their local Hollywood Mall. Like any young boy in 1981, Adam was fascinated by an Atari video game display being played by a small group of older kids. Reve Walsh innocently left her son to briefly watch the gamers play while she inquired about a lamp just a few aisles away. In the seven minutes she was gone, a Sears security guard responded to bickering amongst the kids by making them all exit the store—including little Adam, who instinctively followed the guard’s orders (and the other children) and exited the nearest door. In that precise moment, Ottis Toole was in the parking lot, just looking for someone like Adam. And unfortunately, he found him.

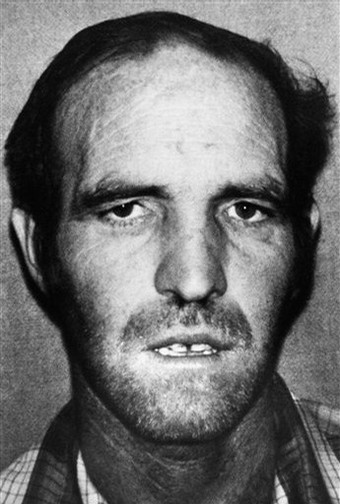

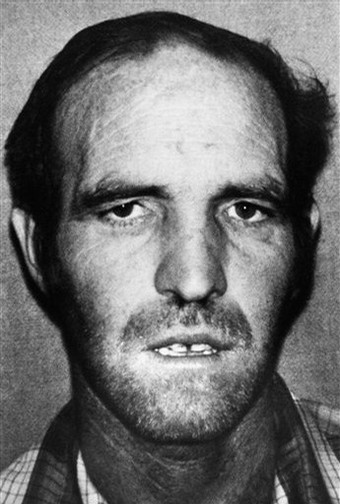

Ottis Toole mugshot, 1983.

Adam was allegedly lured into the stranger’s borrowed Cadillac with promises of toys and candy. Toole, a deviant drifter already convicted of a slew of bizarre and brutal crimes, confessed to abducting the boy with the intent of simply “keeping him” as his own. But when Adam began to cry and panic while driving north along Interstate 95, Toole punched the boy into unconsciousness. Changing plans, he drove the car onto a deserted service road, where he claimed to have strangled Adam to death before decapitating him with a machete he kept under the front seat. On August 10, 1981, a pair of fishermen discovered Adam’s head in a Vero Beach, Florida canal. The rest of his remains have never been recovered, leading credence to Toole’s claim that he incinerated the boy’s body in an old refrigerator.

Despite Toole’s initial confession as early as 1983, Hollywood police bungled the investigation—inexplicably losing Toole’s impounded car… and the machete. It wasn’t until nearly 25 years later, after an independent investigation by Det. Sgt. Joe Matthews at the behest of John and Reve Walsh, that police finally, officially closed the case—naming Ottis Toole as the murderer. While researching evidence files, Matthews had discovered rolls of film—photos taken by crime scene investigators and evidence technicians—that had never even been developed. These photos, when processed, turned out to include chilling, detailed images of the missing Cadillac. One set of photos was particularly damning, as it documented a large presence of blood on the floorboard of the driver’s seat and the carpet behind it—where Toole claimed to have callously tossed Adam’s head before discarding it in the canal. “Traced in the blue glow of Luminol was the outline of a familiar young boy’s face, a negative pressed into floorboard carpeting, eye sockets blackened blank cavities, mouth twisted in an oval of pain,” an excerpt from Matthews’ book reads. After an exhaustive review of the “new” evidence, Hollywood Police formally charged Ottis Toole with the crime in December 2008, and apologized to the Walsh family for the long, painful journey they had endured to that point.

But there’s much more to the Ottis Toole story than just the murder of Adam Walsh. Especially when it comes to his relationship with the even more notorious serial killer, Henry Lee Lucas.

Henry Lee Lucas first met Ottis Toole in line at a soup kitchen in Jacksonville, Florida in 1976. But before joining up with his frequent traveling partner, lover, and confidant, Lucas—a diagnosed psychopath—had already killed before. His first murder, in 1960, was that of his own mother.

Henry Lee Lucas

Lucas was released from prison in 1970 due to overcrowding, but by 1971 he landed in a Michigan penitentiary for the attempted kidnapping of a teenaged girl and for violating his parole by carrying a gun. From there, he was released in August 1975, and took a bus to Perryville, Maryland, where he had a half-sister named Almeda Kiser. He spent the next few years as a hopeless drifter, occasionally working odd construction and mechanical jobs, but unable to work steadily. In 1975, he briefly settled in Port Deposit, Maryland—marrying a woman named Betty Crawford. But within two years, Betty accused Lucas of molesting her two daughters, and he left for Florida—setting the stage for what many believe to be one of the longest serial killing sprees in the annals of American crime.

(Washington Post. October 27, 1983, p. A6)

Beginning in 1978, Lucas and Toole embarked on a series of cross-country murder sprees. Lucas would later claim that during this period he had killed hundreds of people, with Toole assisting him in “108 murders,” by his estimation. Lucas stated that his preferred victims were young white females; Toole preferred men. Their methods of operation included everything from stabbing, shooting, strangulation, and beating to mutilations—with Lucas having been known to decapitate victims and carry body parts with him across state lines on different occasions.

Lucas and Toole went their separate ways on multiple occasions—most notably when the bisexual Henry would “run off” with Toole’s own teenaged niece, Becky Powell—whose murder he would eventually be charged with as well. It was during one of these rare solo periods in 1981 when Ottis Toole murdered young Adam Walsh. Lucas, coincidentally was imprisoned in Pikesville, Maryland between July and October 1981; and as soon as he was released on October 7th, he traveled to Jacksonville, Florida to reteam with Ottis Toole.

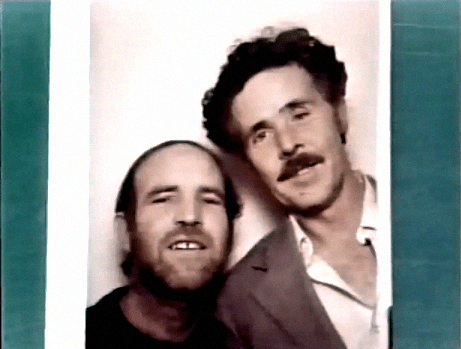

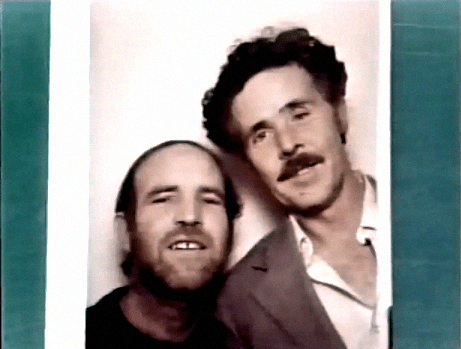

Ottis Toole and Henry Lee Lucas, photo booth print c.1982.

When traveling together, Henry and Ottis were virtually untraceable, making erratic treks from coast to coast. Lucas, on record, later confirmed to Texas prosecutors that in September 1982 alone, the pair had been through Missouri, Indiana, Illinois, Oklahoma… and Maryland.

Criminal profilers in various states found themselves stumped at the lack of motive and pattern in some particularly brutal crimes, as was certainly the case with the Stefanie Watson murder. Serial killers, it was commonly believed, usually work alone. The utter randomness of these crimes was virtually unprecedented, especially when they occurred in small communities.

Lucas was arrested in Texas on June 11, 1983, initially for unlawful firearm possession. He was later charged with killing 82-year-old Kate Rich, with whom he briefly stayed as a boarder, as well as the earlier stabbing death of Ottis Toole’s niece, Becky Powell. While in custody, Henry Lee began to confess to numerous other murders, as well—frequently detailing victims and crime scenes that only the killer(s) would have known. Unfortunately, he also confessed to scores of murders that he couldn’t have committed. Enjoying the extra attention warranted someone who boasts of having killed hundreds—even thousands—of people, Lucas seemingly began copping to any and all unsolved cases presented to him. He would then recant confessions just as frequently, further baffling prosecutors.

In November 1983, the “Lucas Task Force” was created in Williamson County, Texas, for the purpose of coordinating with police agencies across the country. So vast and wide were Henry’s claims, that Texas authorities gave out-of-state detectives the opportunity to interview Lucas for their own cases. One of those agencies, I’ve learned, was Prince George’s County Homicide.

Meanwhile, Ottis Toole was finally behind bars himself. Initially arrested for arson, (Toole was also an admitted pyromanic—or “powerful maniac”, as he believed was the correct term) it was a jailhouse tip from Henry Lee Lucas that shined a more sinister light on his onetime partner. In April 1984, Toole was convicted and sentenced to death in Jacksonville for the murder of 64-year-old George Sonnenberg—whom Toole had barricaded into his own home before setting the house on fire—a crime he’d committed back in January 1982. He was also found guilty of the February 1983 strangulation murder of 19-year-old Silvia Rogers, a Tallahassee, Florida resident, and received a second death sentence. On appeal, however, both sentences were commuted to life in prison.

Back in Texas, the Lucas Task Force investigation was well under way throughout 1984, when it began to receive criticism for becoming “a veritable clearinghouse of unsolved murder.” In fact, Police officially “cleared” 213 previously unsolved murders via Lucas’ confessions. Speaking out of the proverbial other side of his mouth, however, Lucas claimed that he confessed only because doing so improved his prison living conditions—and because he received preferential treatment rarely offered to convicts. It was at this time that Vic Feazell, an ambitious young District Attorney in Waco, Texas, launched a large scale investigation into the veracity of Lucas’ confessions. The result was the “Lucas Report”, an extensive timeline documenting the confirmed travel movements of Henry Lee Lucas (and Ottis Toole) that conclusively disproved many of Lucas’ confessions. In a typical instance, the report showed Lucas cashing checks in Florida while at the same time confessing to a murder in Texas.

Vic Feazell and Henry Lee Lucas (Photo: vicfeazell.com)

But ironically, it’s Feazell’s timeline that may actually implicate Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole in one of the few murders that they didn’t confess to—the Stefanie Watson murder.

Feazell’s timeline shows no record of Lucas’ whereabouts during July 1982—the time when Stefanie Watson was killed. It does, however, document several of Lucas’ travels throughout Maryland.

The report includes grim information about Lucas’ methods, which clearly match the Stefanie Watson murder profile.

Take a closer look at that first page—the timeline of travel movements. Did you notice anything else particularly interesting in regard to Stefanie Watson? Remember the vehicle the witness reported having seen on Larchdale Road that night? It was described as “a 1975 to 1978 Ford LTD, medium to dark green body with a green vinyl roof.” According to multiple entries in Vic Feazell’s notes, Lucas purchased a 1973 Ford LTD on January 9, 1982:

One note mentions it having been a brown car. Whether it was or not, it’s fairly easy to imagine a brown 1973 Ford LTD being mistaken for green in the darkness on Larchdale Road.

And the 1973 model did offer the darker vinyl top, a distinctive feature that the witness pointed out. What do you think? Could a 1973 Ford LTD be mistaken for a 1975-78 model?

With all these things considered, let me go ahead and spell this out completely. What are the odds that the two men seen driving the Ford LTD that night were NOT Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole?

Could it really just be some amazing coincidence, and that two other guys—one of whom eerily fits the description of the 6’1, 195 lb. Ottis Toole—just happened to be driving an equally similar Ford LTD, and tossed a severed head out into a wooded area? The unique and horrific profile of this murder matches that of Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole, who were known to have been traveling together through Maryland at that time, in that vehicle. It can’t be a coincidence.

What initially sounded implausible at best now strikes me as the almost certain answer to the question that has haunted Laurelites for the past three decades: who killed Stefanie Watson?

Back in March, I contacted Laurel Police in hopes of finally learning the basics of this case, and separating the facts from the many rumors I’d heard as a child. Most importantly, I wanted to find out if in fact the case was still open—and hadn’t been quietly solved at some point over the last several years. I explained that I was writing a piece for Lost Laurel on the approaching 30th anniversary of the murder, in the context of the countless Laurel businesses—most now gone—that had spread the word about this horrific crime.

I had the pleasure of speaking to Chief of Police Richard McLaughlin, who confirmed that the case was indeed still open to the best of his knowledge; he also confirmed that Prince George’s County assumed control of the case when the partial remains were discovered.

I wasn’t surprised to learn from Chief McLaughlin that all of the original investigators have since retired, but I was surprised (and flattered) to find out that he was familiar with Lost Laurel! He was also kind enough to not only encourage me to follow up with Prince George’s County Homicide’s Cold Case Unit, he even told me what to say when I called. (I had explained that “investigative journalism” isn’t something I do regularly; and despite the seriousness of all this, I actually had to pinch myself to realize that I wasn’t in an episode of Law and Order or The First 48. Having the chance to talk to the Chief of Police of one’s hometown about said town’s most notorious unsolved crime can tend to make one geek out. But I digress.)

Over the next week, I spoke to Sgt. Rick Fulginiti and Det. David Morissette, both of Prince George’s County Homicide. As I did with Chief McLaughlin, I introduced the project and carefully pointed out that I was only nine years old at the time of the murder I was inquiring about, less I suddenly become a suspect myself. Sgt. Fulginiti confirmed that the case was indeed still open, and active. And when Det. Morissette began explaining just a few of the general points that their Cold Case Unit has been investigating, I immediately got the sense that I hadn’t uncovered anything that Prince George’s County detectives didn’t already know. (Go figure). In fact, the very first name Det. Morissette mentioned was that of Henry Lee Lucas.

He confirmed that in 1984, Prince George’s County had indeed sent a team of investigators to Texas to participate in the Lucas Task Force questioning. While their suspicions have always lied with Lucas, they simply weren’t able to conclusively connect him to the crime. Apparently, their visit occurred during a rare moment when Lucas wasn’t in a confessing mood.

Nonetheless, Det. Morissette had some interesting new news to report, and it could be big: his office has “several new items for DNA testing,” and “has been in recent contact” with Stefanie’s family.

Wanting to make sure I wouldn’t only be spreading more rumors and misinformation about this tragedy, I essentially sought an off-the-record endorsement for the conclusion that I’d surprisingly come to on my own. Det. Morissette simply encouraged me to write this piece exactly as I’d planned, adding that it could even jog some long-suppressed memories, or prompt someone to finally come forward with details that they just weren’t ready to share over the past three decades.

So what comes next? Nothing will bring Stefanie back, obviously; and is any of this relevant—particularly since Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole won’t be here to face any charges that might be brought?

Ottis Toole died of liver failure on September 15, 1996. He was 49. Fortunately for society, he had been wasting away in a Florida prison since April 1983—a mere seven months after that witness on Larchdale Road spotted someone who looked awfully like him discarding something in the woods. He was buried in the Florida State Prison Cemetery when no one—relatives or otherwise—would claim his body.

Henry Lee Lucas, likewise, enjoyed only brief freedom after Stefanie Watson’s murder. Locked away in a Texas prison since June 1983, he died of heart failure at age 64 on March 12, 2001.

Stefanie’s complete remains have never been recovered. She has yet to receive a proper burial, or a permanent resting place. There was a memorial service for her, however, shortly after the identification was made. According to Pastor Arthur Mayer, almost 100 people filled the small Seventh Day Adventist Church in Laurel that September afternoon. And there would’ve been more. Originally scheduled for 7:00 PM, Stefanie’s family decided at the last moment to change the time to early afternoon, so her co-workers from the hospital night shift could attend. For many, including the press, news of the change in time came too late.

The hospital also honored Stefanie’s memory with a brief, but moving service attended by almost 60 members of the medical staff, plus friends and family. In a fitting tribute to the young woman who’d comforted so many worried patients there, the family room of the Greater Laurel Beltsville Hospital’s emergency room was officially dedicated to Stefanie Watson.

On September 11th, (a day that would have its own nefarious connection to Laurel 19 years later) the Washington Post ran an obituary column:

If police were to posthumously charge Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole with this murder, perhaps it could bring some long-overdue measure of closure to Stefanie’s family, the way it did for John and Reve Walsh. It could also hopefully bring the memory of the real Stefanie Watson back to the public eye, reminding us that hers was a life worth remembering, rather than just the brutality with which it ended. Henry Lee Lucas and Ottis Toole, if indeed guilty, should finally be identified and held responsible for this horrific crime; and then they should be forgotten.

***

There are a number of people I need to thank for being able to share this story: Laurel Chief of Police Richard McLaughlin, for his time and encouragement; Sgt. Rick Fulginiti and Det. David Morissette of Prince George’s County Homicide, for also taking the time and making the effort to review and share a case that predates their own careers. Most importantly, the writers and editors of the Laurel Leader who originally documented this terrible event between July and September 1982—most notably Karen Yengich, Gill Chamblin, and photographer Doug Kapustin. I’m sure there were more, but unfortunately, not all stories were afforded a byline. Last but not least, the Laurel Library, for continuing to house the only known complete microfilm archive of the Laurel Leader, despite obvious space restrictions. A city’s history is literally recorded in its newspapers—please don’t ever let that archive disappear.